“Eu odeio vir aqui, porque é tão perto.” Abeer Alkhateeb diz-nos que só voltou a este pedaço de estrada porque nos quer mostrar como é já ali. Di-lo enquanto aponta para o horizonte — um horizonte literal e também metafórico. Al-Quds. Jerusalém. Estamos numa rua quase deserta, um carro ou outro, de quando em vez. Ao longe, vê-se a cidade prometida, sol a pôr-se, já cor-de-rosa-laranja, uma luz que só aqui se encontra, na Palestina. Eu fico atrás do meu telemóvel, a captar uma imagem que espero um dia poder esquecer: duas mulheres a olhar ao longe uma cidade que só uma delas pode pisar. “É tão perto”, diz Abeer Alkhateeb. Tão perto que o seu pai, em tempos não tão longínquos, lá ia desde aqui mesmo, onde estamos, até lá, de burro. Tão perto que era lá que ela e a sua família fazia compras, quando era criança: “Nessa altura, nós não sabíamos o que era Ramallah ou Qalandia.”

Depois veio o muro do apartheid. “Quando o muro veio, destruiu tudo.” Famílias foram separadas, vilas atravessadas a meio, gente impedida de visitar os lugares que sempre visitaram. “Todas as vilas [aqui perto] estão rodeadas pelo muro.”, diz Abeer. E estão. Mostra-nos uma vila: cercada. Mostra-nos outra: cercada. E, lado a lado com o muro, vão-se vendo colonatos, aqui e ali, crescendo a cada ano, cada vez mais perto das populações, engolindo cada pedaço de terra. Eu penso para mim: será que, quando cá voltar, estas casas ainda vão existir? Mas não digo em voz alta.

Continuamos de carro por uma estrada que é mais buracos que alcatrão. Abeer Alkhateeb vai apontando para a esquerda e para a direita, para plantações de vegetais de famílias que se recusam a sair, venham estes e outros muros, venha o que vier. Uns metros mais à frente, diz; “É um projeto meu e do Munther [Amira].”, apontando para dezenas de oliveiras jovens, com cerca de três anos, firmes, à beira do muro, como se estivessem a fazer frente ao projeto colonial sionista. Uns metros mais à frente: “Estas oliveiras plantámos há dois meses.”, diz Abeer Alkhateeb. “São os vossos guerrilheiros.”, digo eu, do banco de trás. “Alhamdulillah [graças a deus], nós tentamos.”

Abeer Alkhateeb leva-nos a outra vila atravessada pelo muro. “Yalla”, diz-nos, enquanto abre a porta do carro. Descemos uma colina, sempre com o muro a vigiar-nos lá de cima e, ao fundo, vai aparecendo um e outro miúdo, não mais que 10 anos, a jogar à bola, num descampado, com duas balizas de futebol, com ar de campo abandonado pelo tempo. “Nós fizemos esta coisa estúpida para proteger a terra.”, diz, enquanto nos explica que ela e alguns companheiros decidiram construir com as próprias mãos duas balizas de futebol, há três anos, como forma de prevenir que os sionistas tomassem mais um pedaço de terra. “Um dia, vocês vão voltar aqui e vai haver luzes e umas escadas e um estádio e uma piscina. É uma coisa muito estúpida mas, inshallah [oxalá], o nosso sonho é que continue.”

Eu não acho uma coisa estúpida, digo. E ensaio na minha cabeça como explicar-lhe, sem parecer um branco-lambe-botas, que esta é, na verdade, uma das coisas mais bonitas que vi. Que não há outro lugar no mundo onde tenha aprendido tanto como na Cisjordânia. Não consigo. Fico com isto às voltas na minha cabeça. Não é o ato de construir duas balizas num descampado que é particularmente excecional. Nem as oliveiras junto ao muro que são particularmente saudáveis. Nem a horta à beira de colonatos que é particularmente produtiva.

Horas depois, já de volta a sua casa, na sala de estar, avanço com uma teoria: é que foi aqui que aprendi a ser anarquista. Que aprendi que não precisamos de mais ninguém que nós próprias para cuidar de nós mesmas. Que, mesmo em terra ocupada, oprimida por quem a quer limpar condenando à morte prematura todo um povo, há quem se junte para criar vida. Que, mesmo quando “o governo” só existe no papel, perpetuando a ocupação, ninguém dorme na rua, ninguém passa fome. Que, quando, durante uma pandemia global, ninguém podia sair de casa, as gentes se organizaram em redes de apoio mútuo. Que, quando, depois de 7 de outubro, tantos ficaram sem empregos, coletivamente se angariou fundos para a sua sobrevivência. Que, quando os sionistas demolem casas, abrigos, poços, escolas, há quem as vá construir novamente. Sem precisar de um estado nem ninguém a quem pedir autorização. E não tenho como agradecer isso que aprendi. Abeer Alkhateeb sorri e traduz para o marido, que se senta ao lado. Depois, vira-se de novo para nós e diz: “Aqui, as pessoas organizam-se a elas próprias. Antes de existir ocupação, antes de existir Autoridade Palestiniana, nós já nos organizávamos sozinhas. Não precisamos de autoridade nenhuma.”

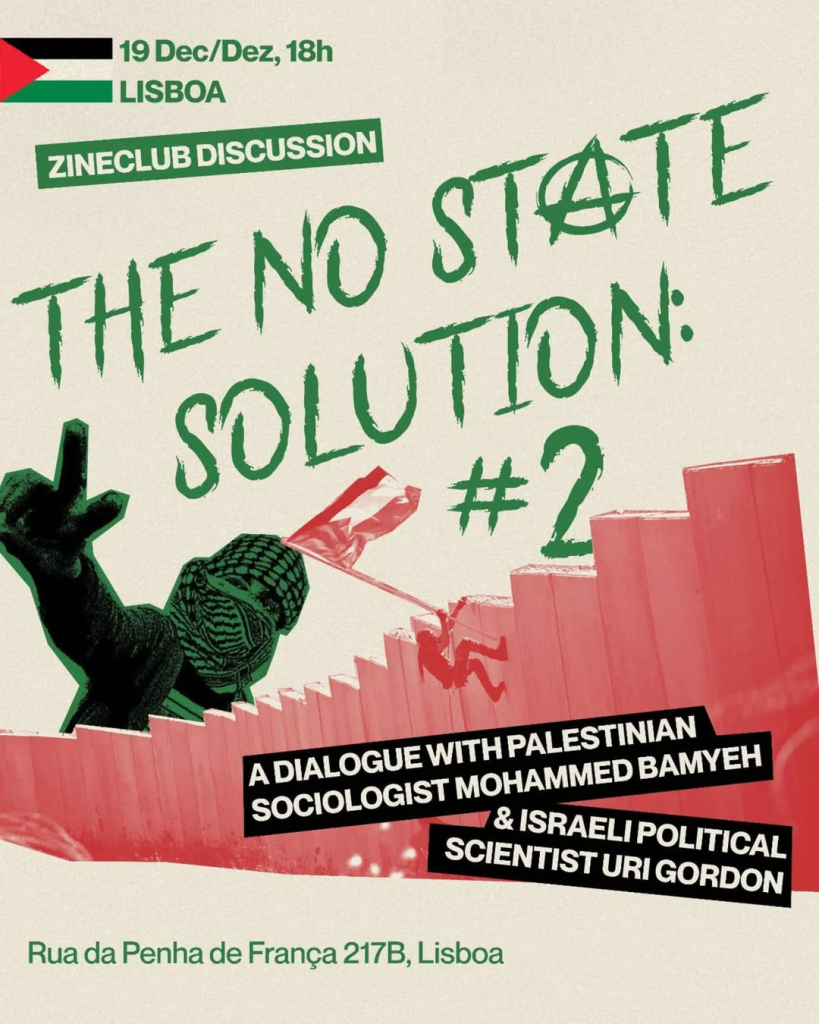

No passado outubro, organizámos uma discussão sobre a “No State State Solution”, uma perspetiva anarquista para “a questão da Palestina”. Como base para a conversa, usamos o diálogo entre o sociólogo palestiniano Mohammed Bamyeh e o cientista político Uri Gordon, que podes encontrar aqui. A conversa resultou no primeiro episódio do Disgraça Podcast. Falámos sobre o que é isto da “no state solution”, do anarquismo como prática ancestral na Palestina, da diferença entre Anarquismo e anarquismo e muito mais. Mas, no fim, ficou uma energia na sala que nos dizia que tínhamos de repetir.

Por isso, a pedido de muita gente, amanhã, 19 de dezembro, temos a segunda edição da conversa “The No State Solution”, às 18h00 na cantina. Vem e traz uma pessoa amiga também.

Na agenda dos próximos dias da Disgraça:

Quinta, 19 de Dezembro: Conversa #2 “The No State Solution” + benefit para o project kapak

17:00-23:00: benefit tattoos para kapka

18h00-20h00: conversa #2 “The No State Solution”

20h00: Jantar

20h00-22h30: Concertos benefit para kapka (Reduce + Snow Bungalow + Nite Chimp)

Sábado, 21 de Novembro:

Benefit para a compra coletiva da Disgraça

17h: 5 concertos (The Smoking Aliens + The Orange Buzz Band + Dead Poets + Menta + Taxonomy)

20h: Jantar

Segunda, 23 de Dezembro:

DIY Monday, a partir das 17h.

Agenda fora da Disgraça: dois benefits para angariar dinheiro para a compra coletiva da Disgraça, em Londres!

Maneiras de ajudar na compra da Disgraça

- Doa na nossa companha online do GoFundMe, ou então se preferes doar de forma anónima recurrentemente, através do nosso Liberapay

- Organiza benefits no teu centro social local! Se precisares de ajuda entra em contacto connosco: disgraca@riseup.net

- Podes fazer um empréstimo pessoal sem juros e flexível: disgraca@riseup.net

- Partilha as nossas zines e material, acessíveis aqui, e as campanhas online nas tuas comunidades!

Beijocas!

Ricardo

[English]

“I hate coming here, because it’s so close”, tells us Abeer AlKhateeb that only came back to this stretch of road to show us how close it is. She says it while pointing towards the horizon – a literal but also a metaphorical one. Al-quds, Jerusalem. We’re in an almost empty road, a car passing here and there, sometimes. In the distance, one can see the promised city, the sun setting already yellow-cum-pink, a kind of light one can only find here, in Palestine. I’m using my cellphone, trying to capture an image that I hope one day I’ll be able to forget: two women looking at a city that only one of them can set foot in. “It’s so close”, says Abeer Alkhateeb. So close that her father, who once upon a not so distant past, would go all the way there from exactly the point we stood at, on a donkey. So close that it was there that Abeer and her family would do groceries, when she was a child. “Back then, we didn’t know what was Ramallah or Qalandia”.

Then came the apartheid wall. “When the wall came, it destroyed everything.” Families were separated, villages cut in half, people separated from visiting the places that they had always visited. “All villages [nearby] are surrounded by the wall”, says Abeer. And they are. She shows us one village: surrounded. Shows us another: also surrounded. And, side by side with the wall, we see settlements, here and there, growing each year, closer and closer to the Palestinian villages, swallowing ever more land. I think to myself: could it be that, when I come back next time, these houses will no longer be here? But I don’t say it out loud.

We continue driving by car through a road that has more holes than tarmac. Abeer Alkhateeb keeps pointing out to the left and to the right, to the farm crops of families that refuse to leave, come whatever walls, come what may. A few meters further on, she says: “This is a project of mine and Munther [Amira].”, pointing to dozens of young olive trees, about three years old, standing firm on the edge of the wall, as if they were standing up to the Zionist colonial project. A few meters ahead: “We planted these olive trees two months ago”, says Abeer Alkhateeb. “They’re your guerrilla fighters”, I say from the back seat. “Alhamdulillah [thank god], we try.”

Abeer Alkhateeb takes us to another village cut in half by the wall. “Yallah”, she tells us while she opens the door of the car. We go down a hill, always with the wall watching over us from above and, in the background, one or two kids, no more than 10 years old, playing football in a field with two goals, almost like a field abandoned by time. “We did this stupid thing to protect the land”, she says, while explaining to us that she and some of her companions decided to build two football goals with their own hands, some three years ago, as a way of preventing Zionists from taking over more of their land. “One day, you’ll come back here and there will be lights, and stairs, and a stadium, and a swimming pool. It’s a very stupid thing, but, Inshallah, our dream is that it will continue.”

I don’t think it’s stupid, I say. And I go over in my mind how to explain to her, without sounding like a white bootlicker, that this is, actually, one of the most beautiful things I’ve seen. That there’s no other place in the world where I’ve learned as much as in the West Bank. I can’t say it. It keeps going round and round in my head. It’s not the act of building two football goals in a field that is particularly exceptional. Nor are the olive trees next to the wall particularly healthy. Nor the vegetable gardens next to the settlements that are particularly productive.

Hours later, back at home, in the living room, I come up with a theory: it was here, in the West Bank, where I learned that I was an anarchist; that I learned we don’t need anyone other than ourselves to take care of ourselves; that even in occupied land, oppressed by those want to cleanse it by condemning an entire people to premature death, there are those who come together to create life; that, even when “the government” only exists on paper, perpetuating the occupation, nobody sleeps on the street, no one goes hungry; that, when during a global pandemic, when no one could leave their homes, people organized themselves into networks of mutual support; that, when, after 7th of October, so many were left without jobs, they collectively raised funds for their survival; that when Zionists demolish houses, shelters, wells, and schools, there are those who will build them again. Without needing a state or anyone to ask for permission. And I can’t thank them enough for what I’ve learned. Abeer Alkhateeb smiles and translates to her husband, who sits next to her. Then she turns again back to us and says: “Here, people organize themselves. Before there was an occupation, before there was a Palestinian Authority, we organized ourselves. We don’t need any authority.”

Last October, we organized a conversation about ”The No State Solution”, an anarchist perspective for the ‘question of Palestine’. As a basis for the conversation, we used the dialog between the Palestinian sociologist Mohammed Bamyeh and the political scientist Uri Gordon, which you can find here. This conversation resulted in the first episode of the Disgraça Podcast. We talked about what the “no state solution” is, anarchism as an ancient practice in Palestine, the difference between Anarchism and anarchism, and much more. But, at the end, there was this energy in the room that was asking for us to do it again.

hat’s why, at the request of many people, tomorrow, December 19, we have the second edition of “The No State Solution” conversation, at 6pm in the canteen. Come along and bring a friend too.

Next days in Disgraça:

Thursday, 19 December:

Conversation #2 “The No State Solution” + benefit for kapka

17h00-23h00: benefit tattoos for kapka

18h: Conversation #2, “The No State Solution”

20h00: Dinner

21h: Benefit concerts for kapa (reduce + nite chimp + Snow Bungalow)

Saturday, 21 December:

Benefit for the purchase of Disgraça

17h00: 5 concerts (The Smoking Aliens + The Orange Buzz Band + Dead Poets + Menta + Taxonomy)

Monday, 23 December:

DIY Monday, starting at 5pm.

Next days outside of disgraça: 2 fundraisers for collectively purchasing the space in London!

Ways to help us collectively buy Disgraça

- Donate through [our online GoFundMe campaign]https://gofundme.com/disgraca), or if you prefer recurrent anonymous donations, then through our Liberapay

- Organize benefits in your local social center! If you need any help, reach out to us at disgraca@riseup.net

- Give an interest free solidarity loan! disgraca@riseup.net

- Share our zines and other materials we might have (you can find them here), as well as our online campaigns on your communities!